The Better Challenge: Hugo’s comeback took a team. Now he’s challenging others to help fight cancer.

.png) When a rugby-mad youngster was given a life-altering medical diagnosis, he learned the true value of a team.

When a rugby-mad youngster was given a life-altering medical diagnosis, he learned the true value of a team.

Three years prior to 11-year-old Hugo Kulscar being told he had cancer, he had lost his grandfather to acute myeloid leukemia, a cancer affecting the blood and bone marrow.

“And so cancer was a topic that, even as an 11-year-old, I knew a lot about,” Hugo, now a 17-year-old apprentice carpenter, says.

“Since the day I was born I had been around him in hospital. He was in and out three times, beat it three times, and then it came back, and he died.

“So, when I was told I had cancer, I was in shock. I thought that was it for me. All I knew was that you could die from it, because that’s what happened to my grandfather.”

Hugo with mum Denai and dad FrankieIt was during a Year 6 maths class that Hugo had felt a lump on the back of his neck. Being a keen rugby player, he had originally thought nothing of it.

Hugo with mum Denai and dad FrankieIt was during a Year 6 maths class that Hugo had felt a lump on the back of his neck. Being a keen rugby player, he had originally thought nothing of it.

The next night, a Friday, he played a game of rugby but felt listless and performed poorly. On the Saturday, he made up for it with a man-of-the-match performance at a school rugby match. On Sunday, after a two-hour training session for an upcoming state championship, he told his mum he had found a lump on the back of his neck.

His doctor sent him for a blood test, concerned about glandular fever. Blood was taken on Wednesday morning, and by Wednesday afternoon he was called to hospital to be told he was suffering acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL).

“I remember my mum was devastated,” Hugo says. “We were all in shock. After my grandfather’s death we were all starting to feel like we could get on with our lives, then this happened.”

Supported by a team

During nine months of intense therapy, Hugo was treated for a 15-centimetre blood clot in his brain and endured severe burns during several rounds of chemotherapy, losing a quarter of his body weight.

“I really wasn’t feeling too well,” he says. But it was his desire to play footy again with his U11 team that became his biggest motivation to get better.

“What drove me most was to get back to playing footy again. It was one of my biggest drivers when I was sick – I don’t think I coped with being off the field, to be fair.

“That whole two years that I was not playing I literally just watched my older brother Noah play – I couldn’t watch my own team. I went to watch them once, and I started shaking and I told mum I wanted to leave – I didn’t want to watch them till I could be back playing.”

During that time Hugo’s rugby community gathered around him.

A few of the old boys from his school were coaching Noah, 15, and his team and they took him under their wing.

“They asked me to help them with coaching, to be the waterboy, etc. That was really important, because it kept me in the game. It gave me some element of a normal life.”

They even shaved their heads in solidarity with him.

That structure, motivation and purpose, Hugo has since discovered, is a vital ingredient typically missing from the lives of most children who have come through cancer treatment.

Mentally tough, physically strong

Hugo says 2018, the year of his treatment, was the toughest year of his life, mentally as well as physically. He’d gone from being a sporty schoolkid playing rugby at a regional representative level to a new high school student who felt disconnected from his mates.

“I was a bit petrified at school,” he says. “It’s not my mates’ fault, but you disconnect because you can’t do what they do.”

“The rugby team gave me something to belong to. Outside of that, it wasn’t a nice time, socially.”

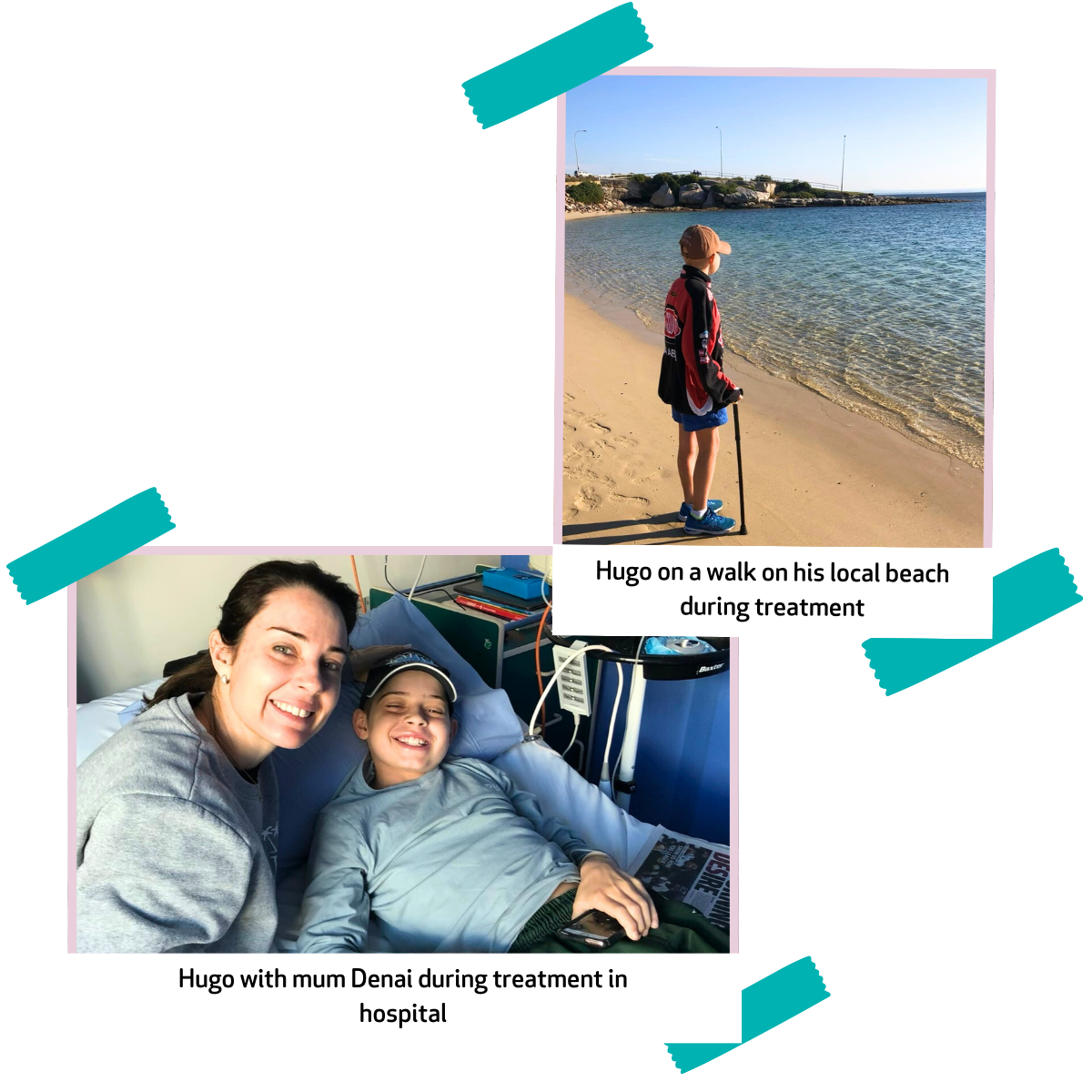

“When I was sick, what forced me to keep moving was little exercises – even if it was just walking to the beach. For me dad was the one who pushed me to not feel sorry for myself – to keep going.

“I’d have two months in hospital and a week at home – and mentally I wasn’t feeling good, and I’d be thinking, ‘what can I do? I’m not at school with my mates?’ and I’d be stuck at home. He sort of kicked me up the backside and would say ‘if it’s a beautiful day I want you to go to the beach, I want you to sit there and get out of the house, and even doing those little things made such a big difference.”

Hugo never even called his leukaemia ‘cancer’ preferring to call it an ‘injury’ he needed to recover from.

“He looked at it like he was out of the game with a footy injury, and just needed time to heal and rehab,” says his proud dad, Frankie. “It was this kind of mental attitude which helped him through his treatment and fight cancer.”

During lockdown, Hugo would hop out of bed at 5am every day to train at the local oval, along the Coogee coastline, and up and down Sydney’s infamous Coogee stairs. Then he’d have another training session every afternoon.

His sessions included weights, running, body weight workouts and more.

“I loved the discipline of it,” he says. “I loved waking up at that time – it felt like it gave me an edge. I knew I had to work harder than anyone else to get back to where I was on the rugby field.”

“What happened in my past motivated me to train hard. It taught me how strong I was. And mentally, it made me stronger. It meant I could handle setbacks. It made me much more resilient on and off the football field.”

The Better Challenge: The magic of movement

Hugo is now playing 3rd Colts for Randwick Rugby Union Football Club. His team recently won the NSW Junior Rugby Union State Championships in Concord, coached by The Kids’ Cancer Project CEO – and former Wallaby – Owen Finegan.

He leapt at the opportunity to become an ambassador for the Better Challenge, which tasks participants with fundraising by taking on 90 kilometres throughout September.

His own journey has proven to him the essential nature of exercise during cancer treatment and recovery, and he credits exercise with helping him fight cancer.

.png)

Hugo wants others to take on the Better Challenge – and help raise vital funds for cancer research in the process - so kids like him can have better and kinder treatments and care.

Rather than suffering some of the many potential side effects of leukaemia treatment, Hugo is now a perfectly healthy 17-year-old. But the scars are still there.

“I think it has physically [set me back] - a lot of people ask me do I feel like I’m the same? But I don’t think you’re the same again because you’ve been battered by the treatment.

“I don’t feel sorry for myself for anything - I get up and get going again – and it can be hard for some kids mentally to get up and get going again.”

That’s why he says he’d like further research to be enabled, to reveal how other children with cancer can enjoy such a positive outcome through the magic of movement.

Research such as that of Dr David Mizrahi, an award-winning exercise oncology researcher, whose research into investigating the role of physical activity in children impacted by cancer needs vital funding to help kids like Hugo. Dr Mizrahi is a Col Reynold’s Fellow, who was named Accredited Exercise Physiologist of the Year for 2023 by Exercise & Sports Science Australia (ESSA). His work in this space is being funded by The Kids’ Cancer Project.

“Research is important first of all because I don’t want kids going through the treatment that I did,” he says. “The knowledge that comes from research is the only thing that will save kids from suffering the trauma that I did.

“A lot of kids I know have come out of the treatment mentally or physically not as good as I have and have had a hard time figuring out where to start their life again.

“But if they didn’t have that trauma, if they were stronger when the treatment ended, the rest of their life would become easier physically, mentally and emotionally. That’s why I think people should get involved in the Better Challenge.