CJ's story

Just two days before their baby boy CJ was diagnosed with neuroblastoma, a cancerous tumour that had grown around his spine, WA parents Chrizette and Callisto had suffered the death of Callisto’s mother from breast cancer.

Neuroblastoma is the most common solid tumour in early childhood. Despite aggressive treatments, including high-dose chemotherapy, the prognosis remains poor for many children, with neuroblastoma accounting for about 15 percent of paediatric cancer deaths worldwide.

For those children who survive, severe lifelong side effects are often present, including motor, cognitive and psychosocial impairments that reduce their emotional well-being and social integration. Thus, more effective treatments for this condition are critical.

So when Chrizette took CJ to hospital in the hope of discovering why her four-month-old son was not having bowel movements as often as he should have been, she was on her own. Callisto was taking care of his mother’s funeral arrangements. Chrizette recalls:

I didn’t have any other support because my mum lives in Canberra and I’m in Perth...

When they told me CJ had cancer, I was holding him. They realised I needed support immediately – I gave CJ to the nurse and I just broke down. I couldn’t break down with him in my arms, but as soon as they took him, it felt like the walls caved in.

My whole world just ended.

When Callisto made it to the hospital, he originally wasn’t sure how to deal with the news...His mother had just died from cancer, so not only was he grieving but he also felt CJ’s cancer was in some way his fault.

Callisto has been an amazing support, but he has a fly in, fly out job so he’s not always here.

- Chrizette, CJ's Mum

As she tried to be strong for her son, particularly during Callisto’s absences, Chrizette found quiet moments to release emotion. Typically this was in bed, after CJ had fallen asleep next to her.

In fact now, over two years later, she still needs that release.

I still break down every day...Every night I cry and cry and just let it out. I know CJ is okay now, and I’m okay. I think it’s just leftover emotions that I didn’t get to feel back then.

I wait until he’s asleep then I curl up on the floor, or kneel by the bed, and just cry as he’s sleeping.

The horror of treatment

Chrizette’s ongoing emotional torment and anxiety is not surprising nor unusual for a parent who has watched their child go through cancer therapy.

It’s nothing less than terrifying, she says, to see how much your child has to suffer in an attempt to survive this dreadful disease.

Read more: "Cage fighting" with neuroblastoma

He had spinal surgery where the surgeon removed as much of the cancer as he could...

CJ needed a catheter for five months after that, and lots of medication. They didn’t start chemo immediately as they thought they might have removed the entire mass, but then it came back.

When he was seven months old, CJ began the first of eight cycles of chemotherapy. He screamed when they put the port into his chest on the first day of the four-day treatment cycle. Where other children would have their chest ports left in, CJ’s had to be re-accessed every day because he was so active. This was enormously traumatic.

Then they’d head home for the three-week break between each cycle, only to have to go through the entire experience again, seven more times over seven more months.

After chemo, cancer cells were still in his bone marrow, so he had six rounds of oral chemo. Chrizette recalls:

Towards the end of the first eight cycles he was really, really bad...

He was pale blue under his eyes, his nails were chipping, he had sores in his mouth. He didn’t want to put anything in his mouth because it was so sore. Because of the chemo, even his poop would burn his skin on the way out. And then the oral chemo gave him really dry skin, so he was just scratching all the time.

Read more: Enhanced polyamine depletion for aggressive childhood cancers

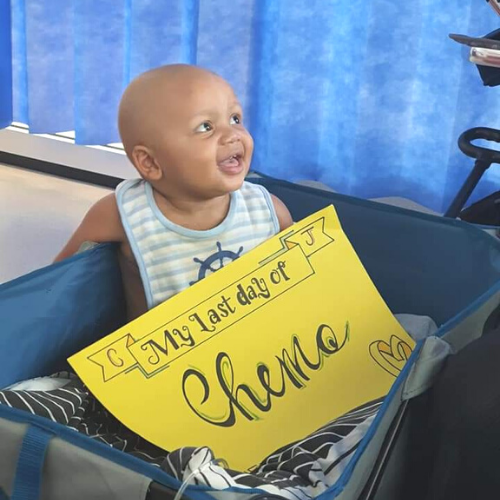

But the treatment meant Chrizette and Callisto got to keep their little boy. CJ was recently declared cancer free.

The bear that made it bearable

While CJ’s treatment experience was awful there were a few bright moments, usually sparked by The Kids’ Cancer Project bears.

During the first cycle of chemo, nurses and doctors had a difficult time putting in the canula. CJ was extremely upset, screaming in pain, until a nurse presented him with a teddy bear donated by a supporter of The Kids’ Cancer Project.

When she gave him the bear, his little face just lit up...This first one was Pirate Bear, and he held the teddy over the port on his chest, as if it was protecting him.

He cuddled that bear for the entire cycle. After that, we took bears everywhere. It helped so much on the days he had to go to hospital, because he knew he might receive a new bear. It took some of the fear away, distracted him and made him feel protected.

Why kids’ cancer is so different

Having seen Callisto’s mother suffering through cancer, then her own son, Chrizette has a unique point of view into the differences between the adult and child cancer experiences.

And it is an enormously different experience for each, she says:

We knew my partner’s mother had cancer, but she was the type of person who didn’t want anybody to worry about her, so she’d act as if she was fine. She’d put on a brave face. And as an adult you can do that. You can hide what you’re feeling and pretend everything is okay. But kids are not programmed like that...

With kids going through treatment you see the reality. Everything is not okay.

Everybody has to be strong for them...It’s exhausting for parents and terrifying for the children. You see all of the raw emotion they go through and it is awful for them.

Why do I support research into kids’ cancer treatments? Because I want to know that one day there will be a treatment that doesn’t attack their immune system, make them so toxic that they have to be kept away from pregnant women, and steal their childhood away.